Celery architecture breakdown

The Celery project, which is often used Python library to run “background tasks” for synchronous web frameworks, describes itself as:

Celery is a simple, flexible, and reliable distributed system to process vast amounts of messages , while providing operations with the tools required to maintain such a system.

It’s a task queue with focus on real-time processing, while also supporting task scheduling.

The documentation goes into great detail about how to configure Celery with its plethora of options, but it does not focus much on the high level architecture or how messages pass between the components. Celery is extremely flexible (almost every component can be easily replaced!) but this can make it hard to understand. I attempt to break it down to the best of my understanding below. [1]

High Level Architecture

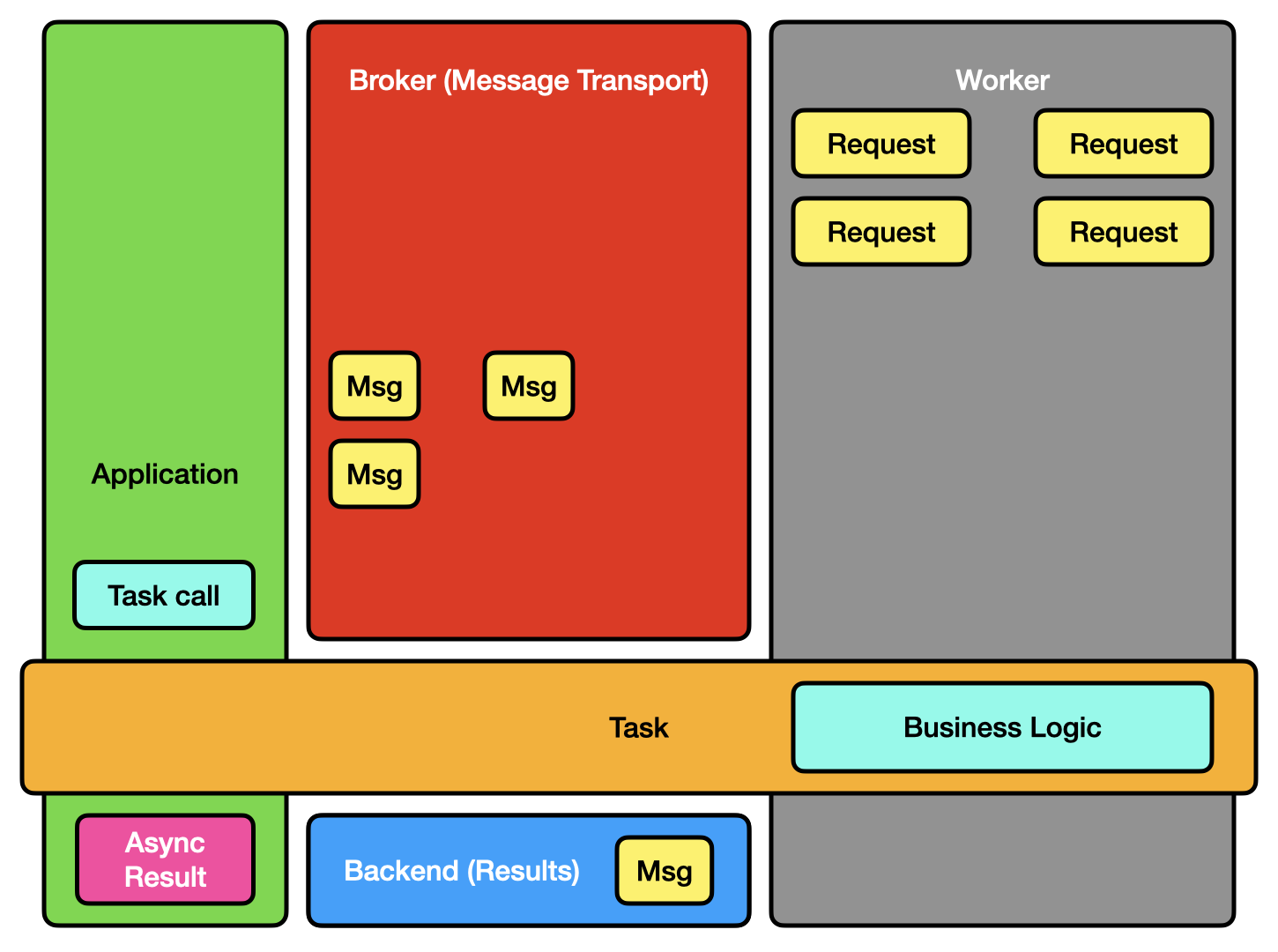

Celery has a few main components [2]:

- Your application code, including any Task objects you’ve defined. (Usually called the “client” in Celery’s documentation.)

- A broker or message transport.

- One or more Celery workers.

- A (results) backend.

A simplified view of Celery components.

In order to use Celery you need to:

- Instantiate a Celery application (which includes configuration, such as which broker and backend to use and how to connect to them) and define one or more Task definitions.

- Run a broker.

- Run one or more Celery workers.

- (Maybe) run a backend.

If you’re unfamiliar with Celery, below is an example. It declares a simple add task using the @task decorator and will request the task to be executed in the background twice (add.delay(...)). [3] The results are then fetched (asyncresult_1.get()) and printed. Place this in a file named my_app.py:

from celery import Celery app = Celery( "my_app", backend="rpc://", broker="amqp://guest@localhost//", ) @app.task() def add(a: int, b: int) -> int: return a + b if __name__ == "__main__": # Request that the tasks run and capture their async results. asyncresult_1 = add.delay(1, 2) asyncresult_2 = add.delay(3, 4) result_1 = asyncresult_1.get() result_2 = asyncresult_2.get() # Should result in 3, 7. print(f"Results: {result_1}, {result_2}")

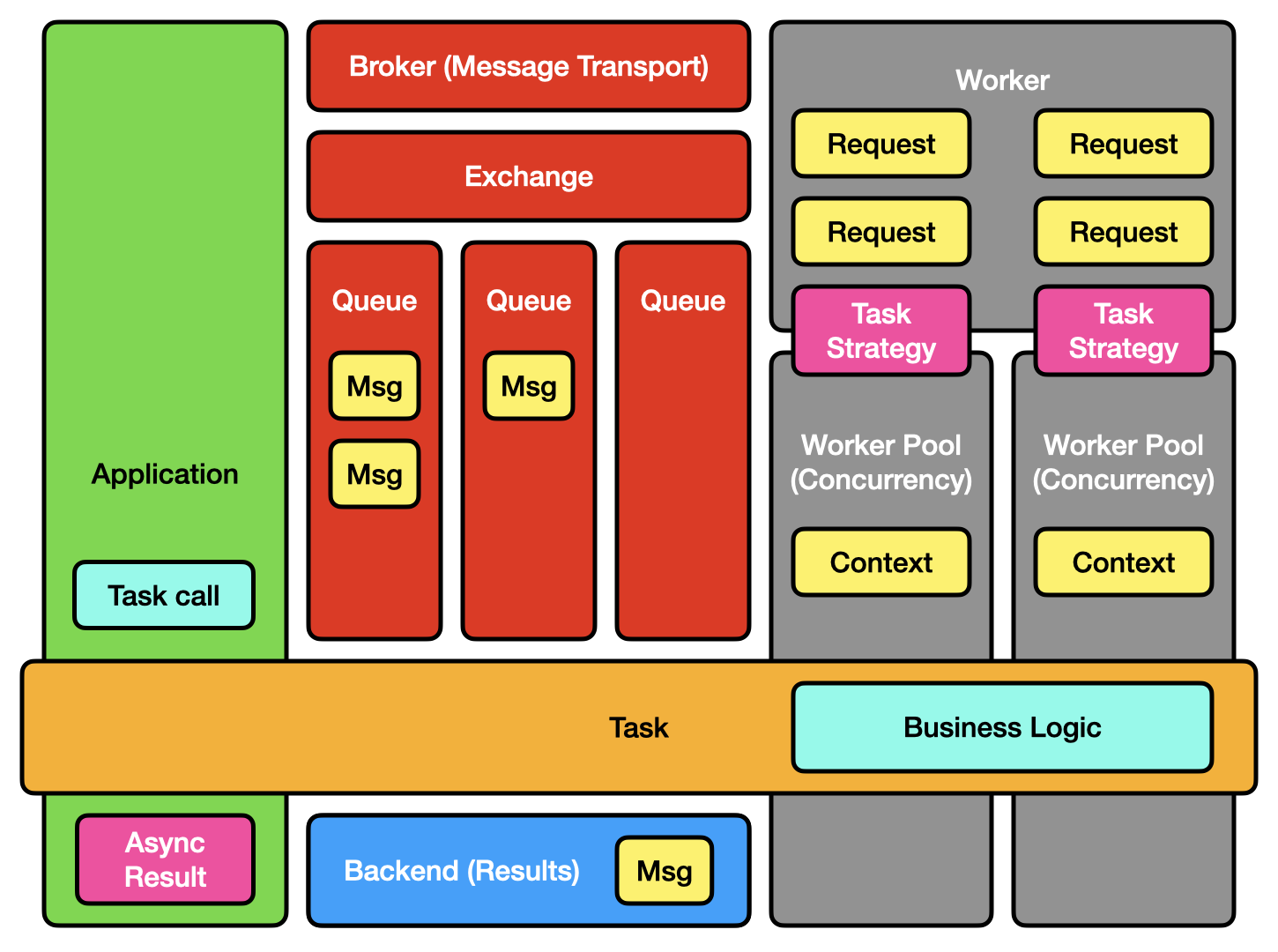

Usually you don’t care where (which worker) the task runs on it, or how it gets there but sometimes you need! We can break down the components more to reveal more detail:

The Celery components broken into sub-components.

Broker

The message broker is a piece of off-the-shelf software which takes task requests and queues them until a worker is ready to process them. Common options include RabbitMQ, or Redis, although your cloud provider might have a custom one.

The broker may have some sub-components, including an exchange and one or more queues. (Note that Celery tends to use AMQP terminology and sometimes emulates features which do not exist on other brokers.)

Configuring your broker is beyond the scope of this article (and depends heavily on workload). The Celery routing documentation has more information on how and why you might route tasks to different queues.

Workers

Celery workers fetch queued tasks from the broker and then run the code defined in your task, they can optionally return a value via the results backend.

Celery workers have a “consumer” which fetches tasks from the broker: by default it requests many tasks at once, equivalent to “prefetch multiplier x concurrency“. (If your prefetch multiplier is 5 and your concurrency is 4, it attempts to fetch up to 20 queued tasks from the broker.) Once fetched it places them into an in-memory buffer. The task pool then runs each task via its Strategy — for a normal Celery Task the task pool essentially executes tasks from the consumer’s buffer.

The worker also handles scheduling tasks to run in future (by queueing them in-memory), but we will not go deeper into that here.

Using the “prefork” pool, the consumer and task pool are separate processes, while the “gevent”/”eventlet” pool uses coroutines, and the “threads” pool uses threads. There’s also a “solo” pool which can be useful for testing (everything is run in the same process: a single task runs at a time and blocks the consumer from fetching more tasks.)

Backend

The backend is another piece of off-the-shelf software which is used to store the results of your task. It provides a key-value store and is commonly Redis, although there are many options depending on how durable and large your results are. The results backend can be queried by using the AsyncResult object which is returned to your application code. [4]

Much like for brokers, how you configure results backends is beyond the scope of this article.

Dataflow

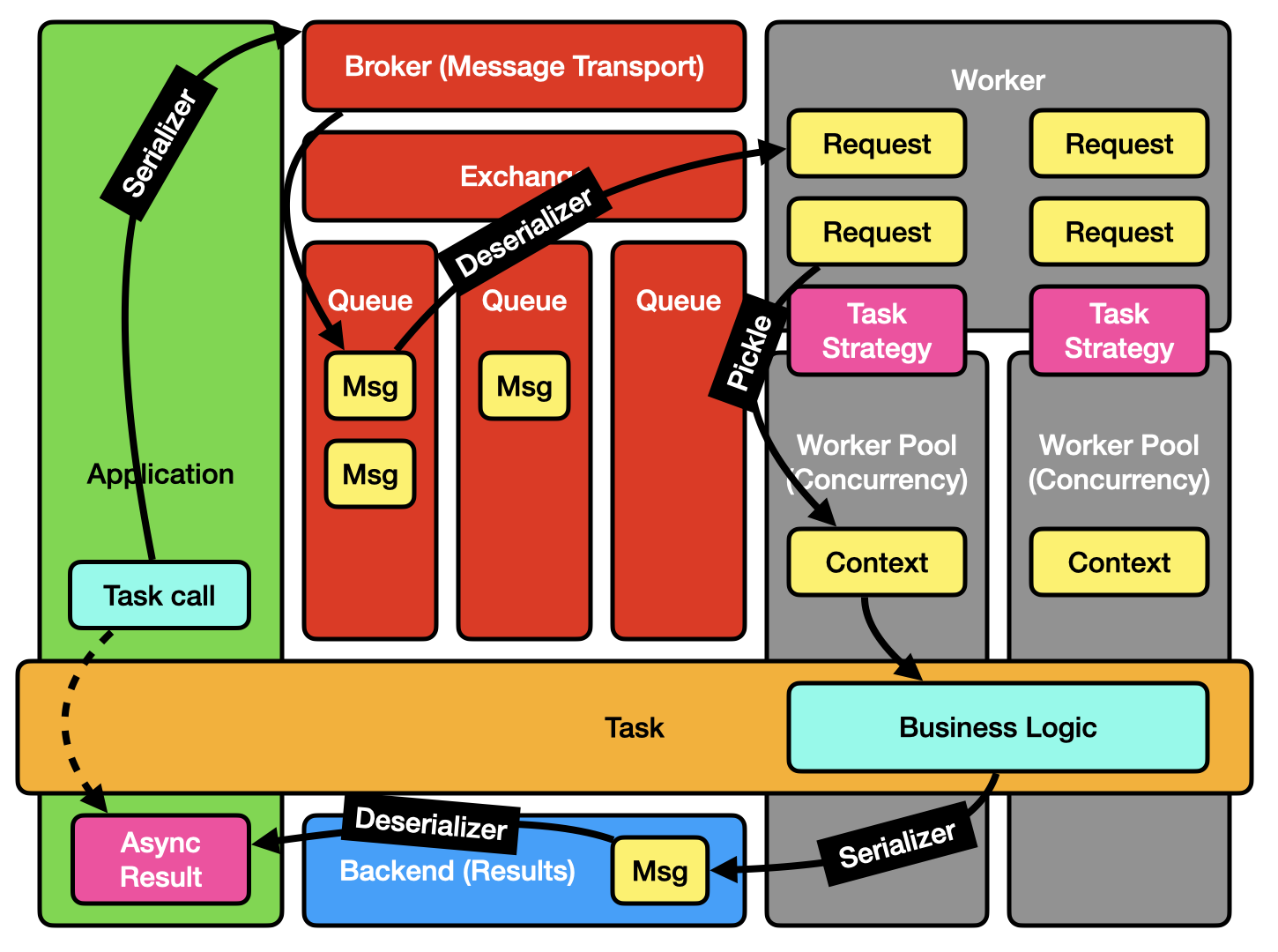

You might have observed that the above components discussed at least several different processes (client, broker, worker, worker pool, backend) which may also exist on different computers. How does this all work to pass the task between them? Usually this level of detail isn’t necessary to understand what it means to “run a task in the background”, but it can be useful for diagnosing performance or configuring brokers and backends.

The main thing to understand is that there’s lots of serialization happening across each process boundary:

A task message traversing from application code to the broker to a worker, and a result traversing from a worker to a backend to application code.

Request Serialization

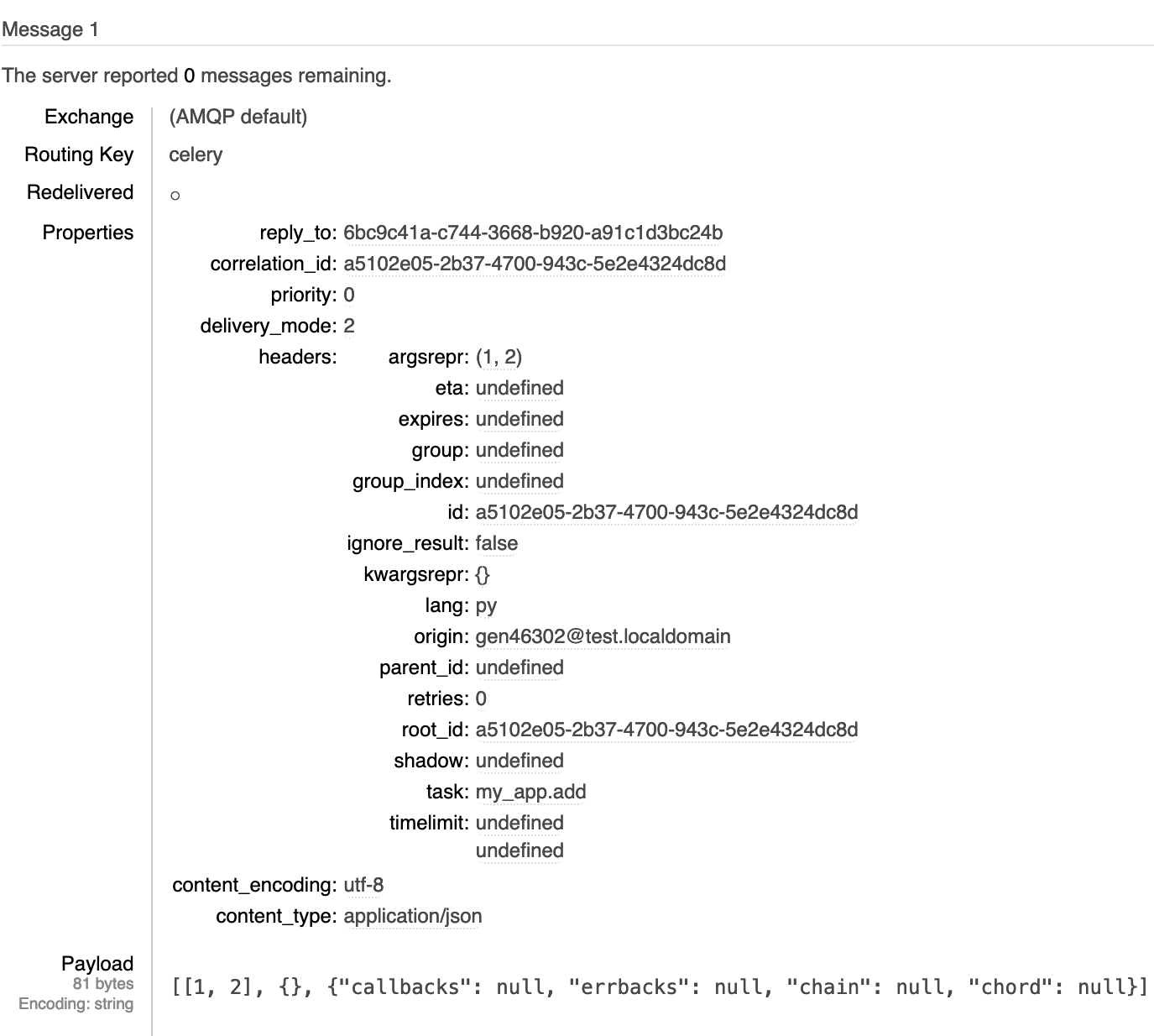

When a client requests for a task to be run the information needs to be passed to the broker in a form it understands. The necessary data includes:

- The task identifier (e.g. my_app.add).

- Any arguments (e.g. (1, 2)) and keyword arguments.

- A request ID.

- Routing information.

- …and a bunch of other metadata.

Exactly what is included is defined by the message protocol (of which Celery has two, although they’re fairly similar).

Most of the metadata gets placed in the headers while the task arguments, which might be any Python class, need to be serialized into the body. Celery supports many serializers and uses JSON by default (pickle, YAML, and msgpack, as well as custom schemes can be used as well).

After serialization, Celery also supports compressing the message or signing the message for additional security.

An example AMQP message containing the details of a task request (from RabbitMQ’s management interface) is shown below:

The example Celery task wrapped in a RabbitMQ message

When a worker fetches a task from the broker it deserializes it into a Request and executes it (as discussed above). In the case of a “prefork” worker pool the Request is serialized again using pickle when passed to task pool [5].

The worker pool then unpickles the request, loads the task code, and executes it with the requested arguments. Finally your task code is running! Note that the task code itself is not contained in the serialized request, that is loaded separately by the worker.

Result Serialization

When a task returns a value it gets stored in the results backend with enough information for the original client to find it:

- The result ID.

- The result.

- …and some other metadata.

Similarly to tasks this information must be serialized before being placed in the results backend (and gets split between the headers and body). Celery provides configuration options to customize this serialization. [6]

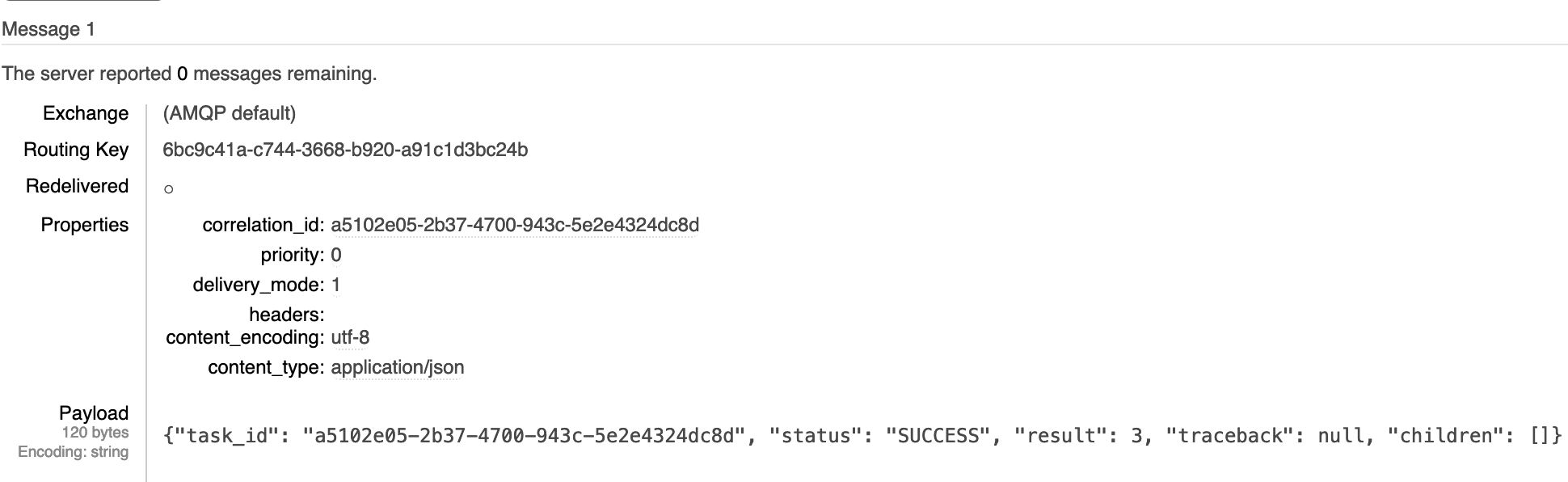

An example AMQP message containing the details of a result is shown below:

The example Celery result wrapped in a RabbitMQ message

Once the result is fetched by the client it can deserialized the true (Python) return value and provide it to the application code.

Final thoughts

Since the Celery protocol is a public, documented API it allows you to create task requests externally to Celery! As long as you can interface to the Celery broker (and have some shared configuration) you can use a different application (or programming language) to publish and/or consume tasks. This is exactly what others have done:

- JavaScript / TypeScript

- PHP:

- Rust

- Go

Note that I haven’t used any of the above projects (and can’t vouch for them).

| [1] | Part of this started out as an explanation of how celery-batches works. |

| [2] | Celery beat is another common component used to run scheduled or periodic tasks. Architecture wise it takes the same place as your application code, i.e. it runs forever and requests for tasks to be executed based on the time. |

| [3] | There’s a bunch of ways to do this, apply_async and delay are the most common, but don’t impact the contents of this article. |

| [4] | As a quick aside — AsyncResult does not refer to async/await in Python. AsyncResult.get() is synchronous. A previous article has some more information on this. |

| [5] | This is not configurable. The Celery security guide recommends not using pickle for serializers (and it is well known that pickle can be a security flaw), but it does not seem documented anywhere that pickle will be used with the prefork pool. If you are using JSON to initially serialize to the broker then your task should only be left with “simple” types (strings, integers, floats, null, lists, and dictionaries) so this should not be an issue. |

| [6] | Tasks and results can be configured to have different serializers (or different compression settings) via the task_ vs. result_ configuration options. |